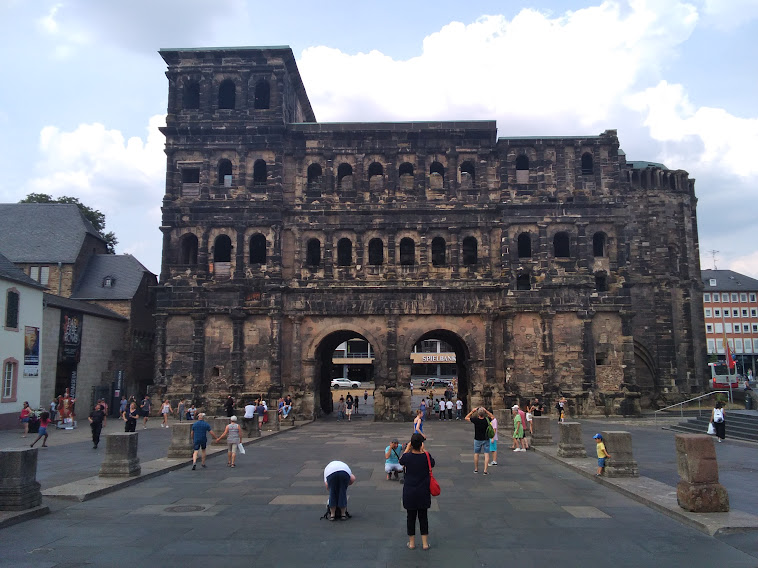

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to visit friends in Southern Germany and join them on a visit to the exhibit “Fall of the Roman Empire” in Trier.

On the evening before we went, we shared a Roman-themed supper, and though the museums left something to be desired, the food was wholly satisfactory. The recipes span a period of at least 500 years, so it is not exactly likely that any Roman ever ate exactly this meal, but the combination fit both the occasion and the (very hot) weather: bread, vegetables, cheese, and a fish course, with a sweet confection shared later in the evening.

We steamed salmon (the fish is not specified in the recipe, and though salmon is very improbable, it is popular and easily available) to serve with a sauce from the Apicius recipe collection:

Ius in pisce elixo (sauce for boiled fish, Apicius 10.1.2)

Pepper, lovage, cumin, small onions, origany, nuts, figdates, honey, vinegar, broth, mustard, a little oil; heat this sauce, and if you wish it to be richer, add raisins.

I first processed together pine nuts, a small onion, some dates, honey, mustard, a dash of vinegar, very little fish sauce, and a bit of the cooking liquid, then seasoned it with pepper, lovage, cumin, and oregano. The result was a sweet mustard sauce with a strong peppery note that everybody enjoyed. Admittedly, different proportions could equally produce something very different.

To go with this main course, we had several vegetable side dishes, the first being an olive relish from Cato’s treatise “On Agriculture”:

Epityrum (Cato 119)

Recipe for a confection of green, ripe, and mottled olives. Remove the stones from green, ripe, and mottled olives, and season as follows: chop the flesh, and add oil, vinegar, coriander, cummin, fennel, rue, and mint. Cover with oil in an earthen dish, and serve.

There is not much to interpret here. I chopped up green and black olives, marinated them in a mix of vinegar and olive oil, and seasoned them with cilantro, mint, fennel, and cumin (but no rue as one of the guests was pregnant).

Then, there was moretum, a strongly garlicky cheese paste known, among other sources, from a poem traditionally (but likely erroneously) ascribed to Virgilius:

Moretum (Pseudo-Virgilius)

(…) He then the garden entered, first when there

With fingers having lightly dug the earth

Away, he garlic roots with fibres thick,

And four of them doth pull; he after that

Desires the parsley’s graceful foliage,

And stiffness-causing rue,’ and, trembling on

Their slender thread, the coriander seeds,

And when he has collected these he comes

And sits him down beside the cheerful fire

And loudly for the mortar asks his wench.

Then singly each o’ th’ garlic heads be strips

From knotty body, and of outer coats

Deprives them, these rejected doth he throw

Away and strews at random on the ground.

The bulb preserved from th’ plant in water doth

He rinse, and throw it into th’ hollow stone.

On these he sprinkles grains of salt, and cheese

Is added, hard from taking up the salt.

Th’ aforesaid herbs he now doth introduce

And with his left hand ‘neath his hairy groin

Supports his garment;’ with his right he first

The reeking garlic with the pestle breaks,

Then everything he equally doth rub

I’ th’ mingled juice. His hand in circles move:

Till by degrees they one by one do lose

Their proper powers, and out of many comes

A single colour, not entirely green

Because the milky fragments this forbid,

Nor showing white as from the milk because

That colour’s altered by so many herbs.

The vapour keen doth oft assail the man’s

Uncovered nostrils, and with face and nose

Retracted doth he curse his early meal;

With back of hand his weeping eyes he oft

Doth wipe, and raging, heaps reviling on

The undeserving smoke. The work advanced:

No longer full of jottings as before,

But steadily the pestle circles smooth

Described. Some drops of olive oil he now

Instils, and pours upon its strength besides

A little of his scanty vinegar,

And mixes once again his handiwork,

And mixed withdraws it: then with fingers twain

Round all the mortar doth he go at last

And into one coherent ball doth bring

The diff’rent portions, that it may the name

And likeness of a finished salad fit. (…)

And yes, that “out of many” is where the phrase e pluribus unum comes from. Again, the interpretation here lies mostly in the kind of ingredients. I opted for feta cheese and processed 300 grams of it with two bulbs of garlic and a generous handful of celery leaves. Then, the resulting paste was seasoned with parsley, coriander, salt, and a bit of olive oil. It needed no vinegar, and again the rue was omitted because of the presence of a pregnant diner.

Then, I prepared one of my favourite misreading: beetroots in mustard sauce

in betas elixas (for boiled chard, Apicius 3.11.2)

Cook the beets with mustard seed and serve them well pickled in a little oil and vinegar.

Note that when Apicius mentions beta, he almost certainly refers to the leaves, not the root. Nonetheless, interpreting this as a beetroot dressing works so well. Basically, take a pound of cooked beetroots, slice them, and dress them with mustard, vinegar, and oil. It’s delicious even if you do not add a little honey (which I do because it is even better). No, this almost certainly NOT what Apicius means.

For our bread, we had must bread, a recipe for an enriched dough recorded by Cato. The original probably gained leavening from the active fermentation of the must. We added yeast because our version used grape juice (having a child and a pregnant adult at the table).

Mustaceus (Cato, 121)

Recipe for must cake: Moisten 1 modius of wheat flour with must; add anise, cummin, 2 pounds of lard, 1 pound of cheese, and the bark of a laurel twig. When you have made them into cakes, put bay leaves under them, and bake.

I added 125g of quark (in lieu of the fresh cheese I think Cato envisions) and about 75g of lard to 1kg of flour, then put in a little anise and cumin, salt, and yeast. After combining all these ingredients in the mixer, I gradually added grape juice until a soft dough resulted. After a leisurely rise, I divided it into individual loaves and baked it, resting on dried bay leaves. The result was so convincing I was asked to do a second batch on Sunday.

For a late dessert, we had – what else? – Cato’s placenta, a rich honey cheesecake. There are surely as many interpretations of this as there are Roman cooks, and I do not pretend to any deep research or broad experience. It was tasty though.

placenta (Cato 76)

Recipe for placenta: Materials, 2 pounds of wheat flour for the crust, 4 pounds of flour and 2 pounds of prime groats for the tracta. Soak the groats in water, and when it becomes quite soft pour into a clean bowl, drain well, and knead with the hand; when it is thoroughly kneaded, work in the 4 pounds of flour gradually. From this dough make the tracta, and spread them out in a basket where they can dry; and when they are dry arrange them evenly. Treat each tractum as follows: After kneading, brush them with an oiled cloth, wipe them all over and coat with oil. When the tracta are moulded, heat thoroughly the hearth where you are to bake, and the crock. Then moisten the 2 pounds of flour, knead, and make of it a thin lower crust. Soak 14 pounds of sheep’s cheese (sweet and quite fresh) in water and macerate, changing the water three times. Take out a small quantity at a time, squeeze out the water thoroughly with the hands, and when it is quite dry place it in a bowl. When you have dried out the cheese completely, knead it in a clean bowl by hand, and make it as smooth as possible. Then take a clean flour sifter and force the cheese through it into the bowl. Add 4½ pounds of fine honey, and mix it thoroughly with the cheese. Spread the crust on a clean board, one foot wide, on oiled bay leaves, and form the placenta as follows: Place a first layer of separate tracta over the whole crust, cover it with the mixture from the bowl, add the tracta one by one, covering each layer until you have used up all the cheese and honey. On the top place single tracta, and then fold over the crust and prepare the hearth . . . then place the placenta, cover with a hot crock, and heap coals on top and around. See that it bakes thoroughly and slowly, uncovering two or three times to examine it. When it is done, remove and spread with honey. This will make a half-modius cake.

The translations this time are not mine. Cato and Apicius were taken from the Lacus Curtius site, Moretum from virgil.org. Note that while translations of most classical Latin texts are available for free online, these are usually old and not always reliable. I certainly do not trust the etxts as they are given here, but provide them for the readers’ convenience. If you want to look at Roman cooking yourself, my preferences are for the Cato translation by Andrew Dalby and the Apicius by Sally Grainger and Christopher Grocock. Both are copyrighted and not available for free download legally, but worth buying if you can.